Becoming AB Inbev

- Integrating and consolidating the financials of the breweries that became AB InBev

- Controllers need common sense and an inquisitive mind

- Controllers should always pinpoint the root cause

Meet the man who integrated and consolidated the financials of all the big breweries that eventually became AB InBev, the first truly global brewer. Mario Matthijs, ex-KPMG, joined TriFinance early in 2014 to set up the CFO Services’ Corporate Reporting practice. In this interview, Mario sheds some light on Brazilian business culture, increased complexity, cash flow awareness, and the qualities of a top reporter.

Mario Matthijs discussing the ins and outs of corporate reporting

Can you tell us a little bit about your background?

Mario Matthijs: ‘I’m an ex-auditor. Joined KPMG immediately after university. I worked 5 years in the regular audit business, as junior and senior, assistant-manager and manager. Afterward, I specialized in the consolidation branch. In 2002, I was approached by the Belgian company Interbrew to lead consolidation. That was a great period because Interbrew was starting to move up the global ladder. Out of a medium-sized Belgian Company eventually grew AB InBev, one of the top 5 consumer goods companies in the world. The biggest brewer in the world.’

The Brazilians are coming!

‘I had the opportunity to be actively involved in all mergers and acquisitions, especially in the integration of accounting and reporting systems of all those breweries in different countries. It started with some German breweries, like Beck’s. In 2004 came the big Bang with the acquisition of AmBev, American Beverages, which was the biggest player in South America, located in Sao Paolo. Since 2004, three Belgian and three Brazilian shareholder families have been leading the multinational.

That must have been quite a culture shock, for both parties.

Mario Matthijs: ‘The Brazilians brought their management to Belgium, with the Belgians adopting the Brazilian style and culture. The culture change was quite radical because the Brazilian style was extremely different. Some concepts were shocking for a typical ‘old-school’ Belgian company, where everybody had his or her own office and a private parking space. The Brazilians all changed that. No offices. They wanted open offices. No dedicated parking spaces. No more taxi drivers on the payroll. The CEO drove an old car.

They installed the concept of meritocracy, focusing on an almost military execution. They introduced a new salary structure, in which the variable pay component became more important than the fixed pay. Zero-based budgeting was introduced. So, your budget for next year was zero. ‘Please, defend what you need and why you need it,’ they said. In a traditional Belgian company, you would get a percentage change from the actuals. That was a totally different mindset. The Brazilians were also very strict, following up on your budget. They made a lot of synergy savings and cost savings. Fascinating, and unseen. There were quite a few social conflicts, that got a lot of coverage in the media, as you will remember.’

You were doing the consolidation. How did that go about in this new culture?

Mario Matthijs: ‘In Brazil, they were ahead of everything, except for financial reporting. At Interbrew, we had already been working with IFRS. We had a decent consolidation environment and robust processes. Our corporate reporting was more advanced. That was very much appreciated by the Brazilians because they wanted world-class efficiency in each and every department. At Interbrew, thanks to the excellent finance managers of the past, the efficiency of financial reporting was amongst the highest, even internationally.

In terms of reporting, we were impacting the AmBev entities more than they impacted us. Also, the holding and headquarters remained Belgian. Consolidation remained to be done from here. The management moved here. The CEO and CFO were based in Belgium. The financial statements were exemplary. For many companies, it was a document they could copy. Because we were firmly ahead of the AmBev entities, the consolidation department remained pretty much the Interbrew consolidation department, whereas the other departments went through heavy transformations.’

How to become a global brewer

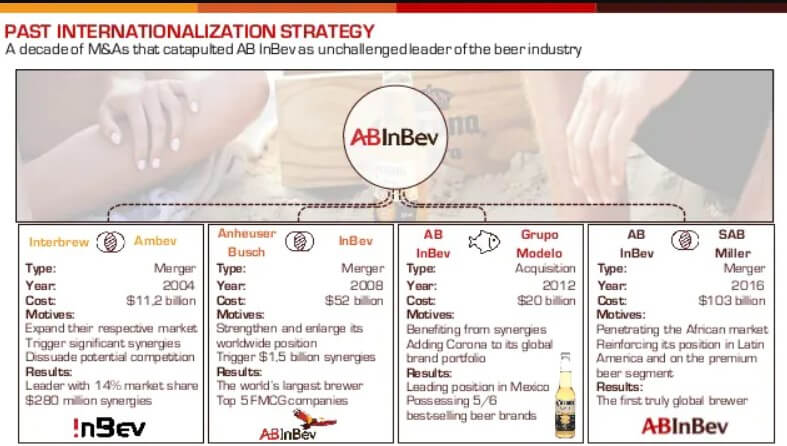

The company actually rolled out an internationalization strategy, engaging in M&A to gain market share.

Mario Matthijs: ‘Yes. In 2007, for instance, we took over Quilmes, the national beer of Argentina. In 2008 there was a huge acquisition with Anheuser-Busch, famous for its iconic Budweiser brand. The company was renamed AB InBev. InBev was the number one brewer in the world. Anheuser Busch was the number Two.

That all fit in a strategy of M&A. Not only focusing on internal but more so on external growth. At the time of AmBev, the Brazilian families had already talked with Anheuser Busch but were not able to reach an agreement, because they were not strong enough. After the merger with Interbrew, becoming InBev, they approached Anheuser-Busch again in 2008, but more aggressively and successfully this time.

So, I spent the last two months of 2008, including the Christmas period, in Saint Louis, Missouri, to consolidate the financials of Anheuser-Busch and integrate it in the consolidated financials of Anheuser-Busch InBev, as the new company was called. The acquisition closed in November 2008. In December 2008 we had to make consolidated statements. With a team of 4 US people and 8 InBev people, we integrated all the entities of Anheuser-Busch in two months’ time. That was fast, but we could not postpone the publication of the results. All the investors expected combined figures.'

Integrating Grupo Modelo in Mexico City

‘The next big integration was with Grupo Modelo (known from the Corona brand) in Mexico, in 2012 if I remember well. We spent 6 months in Mexico City to integrate that business. With AB InBev being the biggest brewer in North America and Latin America, 80 percent of the EBITDA came from the Americas, the company decided to split the headquarters, with the CFO office moving to New York. As I had worked with TriFinance consultants on the Interbrew M&A projects for several years, I decided to join TriFinance to start up the Corporate Reporting practice in April 2014. One year later, AB InBev decided to acquire SAB Miller. Again, I worked for approximately six months on what was a big consolidation and integration. Doing the same as before, but this time as a consultant of TriFinance, doing a final review of the figures, for everything to be consolidated correctly.'

A thirst for knowledge

Did you see the scope of Corporate Reporting change during your years at Interbrew/AB InBev?

Mario Matthijs: ‘Well, companies became more demanding. For many companies, the Accounting and Reporting department is a cost center. Which it is of course. When companies want to save money, they save on cost centers like legal, IT, communication, accounting and reporting. On the other hand, complexity is increasing. With the number of FTE’s dropping and complexity increasing, the Finance function comes under a lot of pressure.'

Are companies aware how much complexity has increased?

Mario Matthijs: 'Let’s say the most knowledgeable companies are aware, but many are not. Complexity has increased on every single item. Because you have new industries, more products, complex products, combined products, different ways to fund. You always need to be proactive: ‘How will we account and report for this, if we don’t want the financial position and the results projecting the wrong image.’ But tight time schedules lead to increased complexity. In the past, accounting records were closed and reports were filed after one month. Now they are wanted after three days. Or at least a first flavor of the result is eagerly awaited.’

Is that technology driven: you must, because you can?

Mario Matthijs: ‘Well, there is the need for knowledge. If you close your P&L statement after three working days, management still has twenty-seven days that month to act. If you only report your figures after three weeks, the next month is gone as well. There’s much more urgency for the figures, and management can intervene a lot faster.’

Did the 2008 crisis have an impact on that timing?

Mario Matthijs: ‘Absolutely. Not only on the timing, also on the quality of the reporting. It changed quite a few things. The importance of SOX increased and the internal controls for accounting and reporting strengthened. Also, the need for fair value presentation on your balance sheet emerged. Until then, there was a kind of general acceptance that financial positions were mostly tax-driven. With IFRS becoming more important, you needed to show the fair value of what your financial position represents, possibly creating a lot of volatility in your figures, but reflecting reality. Any which way, that was a good thing. Investors started to lend more weight to a trustworthy, solid image than on the cost of this increased accuracy.’

Not investing is going backwards

So, what does an increase in more complex products and industries mean for Corporate Reporting?

Mario Matthijs: ‘Don’t forget the acquisitions and mergers, and an inclination towards fast close, because management wants its figures faster, with less people. That’s quite a challenge, because these are conflicting evolutions. That means you really need a good, efficient organization in Reporting. Good controllers, good reporters and consolidators, and of course the tools that allow you to report fast. Having good automated, efficient tools means companies should invest. But they are often hesitant to invest in Accounting and Reporting, because it’s a cost center. They always ask: ‘Shouldn’t we better invest in the market?’'

‘Not investing is going backwards. In people, but also in technology, because technology is getting more efficient. Take the cash flow. In the past nobody cared about the cash flow. Everybody was happy with a balance sheet and an income statement. Since a few years, people understand that the balance sheet and the income statement numbers are not always the ultimate key performance indicators. A company’s most important KPI, these days, is the cash it is generating. You can invoice whatever you want, if you don’t collect the invoices on time, you go bankrupt. If you invest too much in your cash cycle, so that your inventory and receivables are outstanding too long, you get into trouble.'

‘Ten years ago, everybody knew cash flow existed, but it was a very laborious process that demanded a lot of manual exercises. Somewhere in a corner of the office, you saw a corporate guy working in the evening to close down, to make his cash flow balancing, performing all sorts of tricks to get that balance right. In a lot of companies, that is still the case, because 50 percent of companies did not invest in cash flow reporting. Those people are suffering like hell, making all kinds of plugs to make their cash flow work.'

‘On the other side, you have companies where the group controller pushes a button, day by day, with the correct cash flow rolling out. For which company would you like to work? (laughter). They have invested in systems. In tools. They are way ahead of companies that have not invested. So, companies should invest, but in systems and tools that are tailored to their size. A small company does not need a large SAP platform with all kinds of gimmicks. That’s nice to have, but no necessity. Invest in a tool which fits your requirements and then you can optimize the balance between cost and efficiency.’

Research says that organizations have been taking a piecemeal rather than holistic approach to investing, making many of the solutions and technology they adopted to improve close, reporting, and filing processes, ineffective.

Mario Matthijs: ‘Correct. Often there is no vision. Not too many companies ask themselves what they want to achieve in reporting in five years’ time? Sometimes they invest because they hit a wall, they run into trouble and then head over heels they need to invest. They take the first tool that is presented to them. That’s not a good approach. It’s firefighting. Many companies have been acting like that. At a certain moment, they realize it’s not the best tool they have chosen, it’s not the best reporting that comes out. It’s way too manual and not tailored enough. They must invest way too much to keep it working. A strategic approach is necessary here.

‘Management is often aiming for short-term profits, without investing in the underlying fundamentals of many domains, including the reporting domain. At listed companies, you don’t have the time anymore to invest. Investors are expecting that your EBITDA increases, that your financial position improves. They are more focused on revenue contributing or profit contributing projects than on improving the accounting and reporting. If your management’s scope is broad enough, you will have a balanced approach between short term actions improving profit and long-term actions improving the quality of the systems.’

A good reporter must be on top of things. The C-suite wants added value all the time.

Mario Matthijs

Portrait of the good reporter as an inquisitive mind

What are you looking for in a reporter?

Mario Matthijs: ‘Well, first of all: common sense. A good reporter needs a healthy approach to figures and to analyzing figures, talking to the C-suite. You must be on top of things, because the C-suite wants added value all the time. You must know that an entry needs to be balanced, that debit is equal to credit, that asset equals liabilities, but always with a certain degree of management business skills. You must be able to understand what the real problem is.'

'Take the example of a CFO or a VP Finance who says that (s)he does not understand the outcome of a certain accounting policy. What then, is the actual problem: is the accounting policy correctly written and clear to the user? Is it the internal organization that fails to meet the accounting policy? Is it the reporting that is not identifying what should come out? Is it the controllers who fail to do that? Is it a systems issue? A controller should always try to pinpoint the root cause.'

‘I know for instance quite a few companies who do not even have an accounting policy. Then I ask the CFO: ‘How do you want all your affiliates to report correctly if they don’t know what they need to report?’ But it does not stop there. Did controllers get training? It is not because the CFO has a controller in Japan, China, or Australia that this person is knowledgeable. Does he or she understand what the CFO wants him or her to report? Very often that’s not the case. IFRS for instance is evolving so quickly that a training program is a real necessity. And I add ‘How about your systems? Are they correctly configured to sort out the KPI’s you want? That’s what I look for in a reporter: common sense and an inquisitive mind. A good reporter is always able to raise the right questions.’

Related content

-

Blog

ESG - Good Sense for Everybody

-

Article

Five Reasons Talented Candidates Choose Internal Audit

-

Blog

Executing internal audits beyond the traditional scope

-

Article

Takeaways TriFinance ESG Conference: your sustainability journey, from compliance to transformation

-

Article

Bridge builders with an analytical mindset: meet the ERP team

-

Blog

Unveiling the Nuances: Risk vs. Problems in Business